It’s a fool’s errand to try to compete with, or imitate, Nature. Our gut-level, natural design instincts can sniff out most tacky attempts at imitation. Faux “cultured” marble, stamped concrete flagstone, and plastic roses are no substitute for the real thing. We may momentarily be fooled, but like sugar-and-salt-loaded fast food, they are full of empty calories.

On the other hand, it’s foolish not to emulate, if not copy, something made by a craftsman, artist or innovator who may have spent years researching and perfecting a look that you admire––especially if you are just starting out. There is no better, faster way to gain valuable knowledge and expertise than by conscious imitation. There are no great artists in any field, living or dead, who didn’t copy, imitate, or plagiarize their way to greatness and renown.

Van Gogh copied Japanese woodblock prints, Manet, and Cézanne on his way to painting the famous Starry Night. Robert Zimmerman changed his last name (allegedly after poet Dylan Thomas), went to New York and promptly mimicked the “authentic” country singing style of Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, real name Elliot Adnopoz. Elliott was a cowboy wannabe. He was a city kid from the Bronx, who was himself imitating the famous original cowboy minstrel, Woody Guthrie. Bob Dylan, by his own admission, realized this and went around Elliott, directly to Guthrie, and copied Woody’s style first-hand. He would put new words (Blowin’ in the Wind) to the exact melodies lifted from old Carter Family folk songs from the Thirties and they passed as original.

These guys didn’t imitate half-heartedly. They were unashamed serial imitators. They suppressed any ego-driven desire to promote their own premature originality until they really understood the art behind the form they were imitating. But once these artists discovered and understood the terrain of their predecessors, they didn’t hesitate to blaze new trails and claim their own voice, identity and destiny.

So don’t be shy or half-hearted about imitating anything that inspires you. But don’t let imitation become the goal either. Don’t let the blind pursuit of a copy blind you to the infinite possibilities that can arise by deviating from the copy–– because a slave to imitation limits the limitless possibility of innovation.

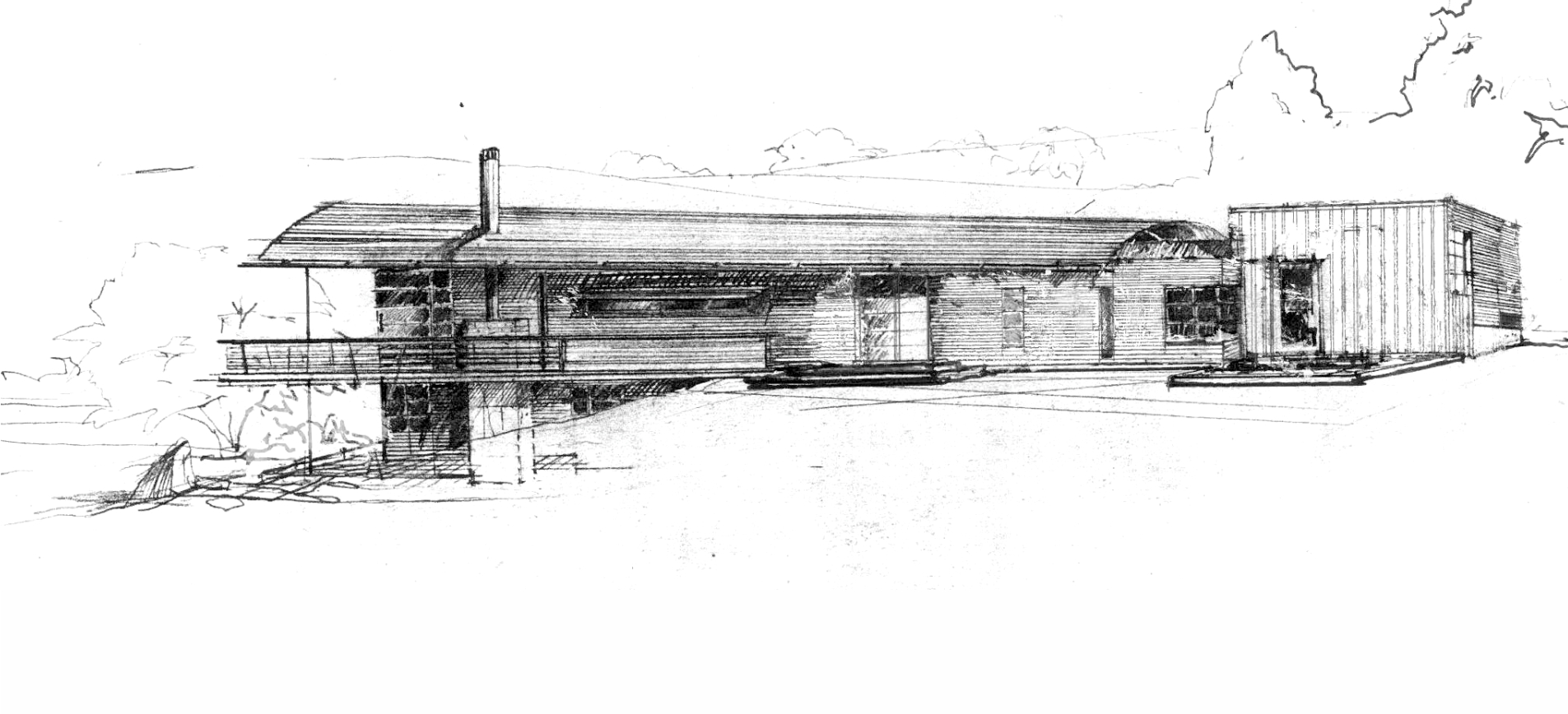

My Hogan/Mayo House Project (pictured below) is influenced directly from an architect that I have long admired – Glenn Murcutt, a world renown, Pritker Architectural prize recipient, from Australia. I was struck by his imaginative use of modest materials and the simple elegance of his designs.

So I tried my hand at using his corrugated metal vocabulary combined with my concrete sensibilities.

Magney House, New South Wales, Australia, 1984 © Anthony Browell, Courtesy the Pritzker Prize Committee

Architect/Designer: Glen Murcutt

Hogan/Mayo House 3 Project, Del Mar, CA 1996

Designer: Fu-Tung Cheng

Hogan/Mayo House 3 Project, Del Mar, CA 1996

Designer: Fu-Tung Cheng

Hogan/Mayo House 3 Project, Del Mar, CA 1996

Designer: Fu-Tung Cheng